The death of Goethe's sentimental hero in The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) brings the tale of love and expiry to a stuttering halt.

When the physician reached the unhappy man, he found him on the floor, not to be saved: his pulse was still beating, his limbs were all paralysed. Over his right eye he had shot himself through the head, brains had oozed out. Uselessly, they opened a vein in his arm; blood flowed and he was still drawing breath.

Werther, the lover, the child, the man of nature, had been just moments before pouring out the fullness of his heart into a final letter to his beloved. The physician reaches him too late - in the following scene he has burst like a balloon. Once the brain is expended, the buoyant Romantic body is cruising for a bruising - too much Geist, not enough machine. Werther's spirit, the anima of the novel, departs....... and his body is reduced to a glitching automaton. The pressure of the soul has built up to such suffocating extent that the body turns red with the snapping of the vital channels, the skull is broken, the brains are oozing out and there is simply nothing else for it to do but die.

Sometimes anatomy is more eloquent than the most poignant drama. Entire epistemologies cascade around Werther's twitching body, and the episode shatters the illusions of the Romantic age in which the subject - the man of feeling - was linked irrevocably to the world through its emotions. In every epoch, not only the architecture of the body, but its style of malfunction reveals our assumptions about its spiritual contents. A body that continues to live in the face of a shot through the brain is one fuelled by the brave motor of the heart as the seat of life. As Goethe shows us, however, a man ruled by the heart alone is horrifying and defective.

The issue of emotional physiognomy is at its most pressing when questions of studying or repairing the body arise. Surgical situations expose the assumptions which precede the calculus of flesh and scalpel, and there are times at which the most singular of bodies unfurls beneath the knife like an illegible text. What if a savvier surgeon had reprogrammed the body to better suit Werther's uncontainable inner world? Some kind of alternative buccal outlet was needed where the mouth and pen had faltered - a kind of valve through which the soul’s huge spring might pour out. A new orifice with the mouth's acrobatic intensity, with the depth and flash of the eyes, but unterritorialised by the senses. Perhaps through such an opening, the modern reader might be able to glimpse the vital kernel which Werther strained so ardently to express.

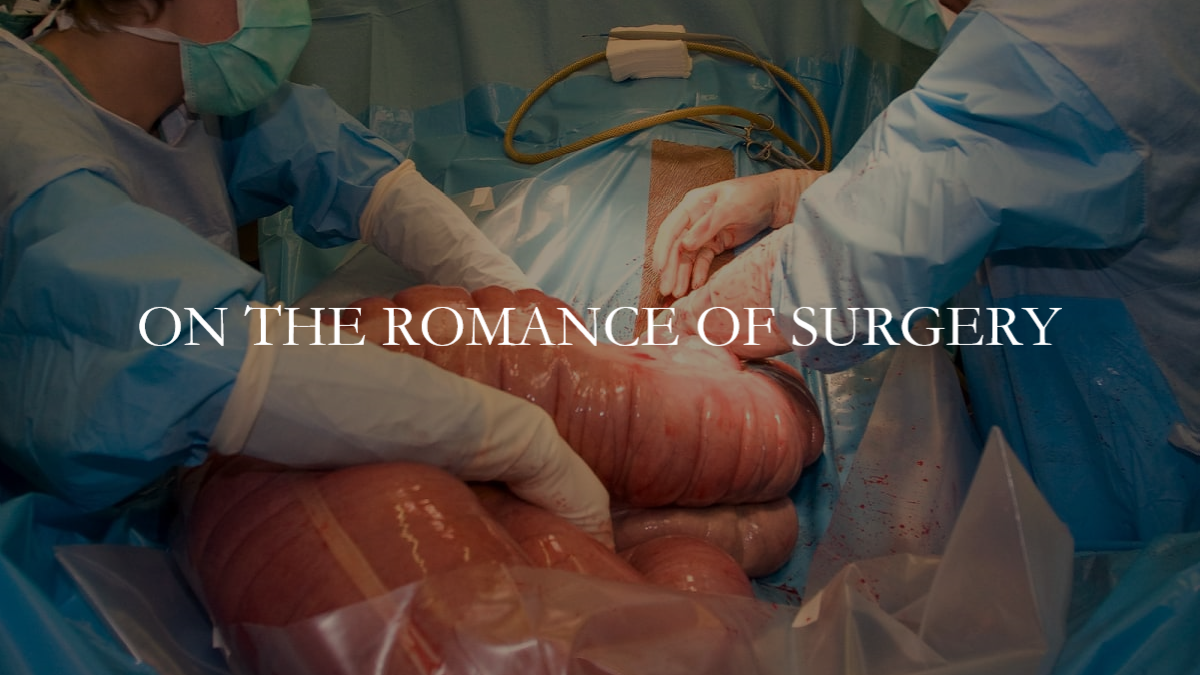

Reading the face, that is reading expression in interpersonal encounters, involves deciphering a configuration of holes on a fleshy surface. The holes themselves are the location of an abstract depth. Surgery, too concerns the interpretation of the holey surface. 'Subjectification,' for Deleuze, 'is never without a black hole in which it lodges its consciousness, passion and redundancies,' and whether this is the black hole of the wound or of the perceptual orifice is of little consequence to visual representation. In this way, surgery performs a facialisation of the body. Unlike the face, the body does not communicate its interior states: this is where the knife comes in, to cut little smiles and winks into the flesh through which, with some expertise and effort, the inside can be divined.

Nowhere is this expressive quality of the surgical incision more apparent than in the permanent stoma, nowadays largely to be found on smoker's throats. The stoma is an artificially-produced hole in the body which allows it to perform its normal functions in the case of failure of an internal mechanism such as the larynx. Halfway between utilitarian opening and the expressive black hole of the facial machine, its potential as a new site of subjectification upon the body has been largely ignored. One might say that what poor Werther lacked was a heart stoma, a mouth located on the chest through which the heart could dribble away without the intermediate machinations of the rational mind. The stoma to which I now turn, however, is of the stomach, a marginalised organ compared with the brain and heart; the symbolic seat not of reason or passion but of irritation, sensibility and a sinister sexuality.

Alexis St. Martin lived and worked in the forests of Canada in a dark century some two hundred years ago. It was fur trade country, and Alexis, slight and nineteen, was a fur-trapper, an occupation which involved transporting pelts through the rivers and the cedar-trees of the northern territories. In 1821 Alexis was accidentally shot at a trading post, at close range, in the gut. The blow blasted through his fifth and sixth ribs, splattering bone splinters everywhere. The resulting wound left a sliver of lung exposed above the surface of the skin, as well as a piece of the stomach sac.

William Beaumont, the local surgeon, eventually arrived at the scene. A recently initiated military doctor aged just twenty-five himself, he was a new resident of Mackinac Island off modern-day Michigan where the incident had taken place. He tidied the wound in situ, expecting, as expressed in his surviving diaries, the damaged organs to buckle under the trauma of the wound. He observes:

I found a portion of the lung as large as a turkey’s egg protruding through the external wound, lacerated and burnt, and immediately below this, another protrusion, which, on further examination, proved to be a portion of the stomach, lacerated through all its coats, and pouring out the food he had taken for his breakfast through an orifice big enough to admit the forefinger.

The bullet had prized open the sleepy eye of the abdomen, the soft internal eggs had been thrown into crisis. No mouth yet, just a scream. But Beaumont’s care would change this. Observing the unusual healing process that the lesion was beginning to undergo, Beaumont invited St Martin back to his home to be privately treated. Through a series of experimental procedures, St Martin would survive. But more importantly, the howl of the wound would be made eloquent. It would be trained into language, it would become a song.

St Martin’s gunshot wound was in fact never to close over completely. It rather solidified into a natural stoma, an external window on the workings of the stomach. Through this peephole, Dr Beaumont would perform the first experiments on the action of the human digestive system. Alexis would be transformed into a living observation chamber, a camera obscura of flesh and blood culminating in a twinkling and expectant eye.

St Martin's stomach vomited up its contents uncontrollably for several days after the accident, the gastric juices spilling up and out of the wound. Eventually, helpless and pink, the stomach grafted itself like an infant rodent onto the work-browned skin of St Martin's outer body as the two healed in tandem, sealing the edges of the wound and producing a direct and permanent opening to the contents of the stomach. Beaumont remarked on the organ's unexpected tenacity: 'The Stomach is not so exquisitely sensible as is represented by anatomists and Physiologists in general.' The stubborn little mouth, or what Beaumont described as 'a natural anus', would eventually adapt aggressively to its newfound vulnerability, sprouting a flap of skin superficially protecting the gaping orifice but still able to be peeled aside by a trying finger.

Over the next several years, St Martin would be taken on as a household servant and experimental subject at once, subjected to increasingly manneristic experiments devised by Beaumont on his newly accessible gastric universe. One day Beaumont even replaced the lint dressing that protected the opening of the wound with raw beef, and in less than five hours the stomach had gnawed it clean off. In order to measure the time it took the stomach to dissolve a range of substances, Beaumont measured the rate of decomposition of the following foodstuffs by dangling them into the hole in St Martin's stomach, on a silk string, as if fishing for trout and sturgoen through a hole in the Mackinac ice.

It received:

a piece of high seasoned à la mode beef

a piece of raw salted fat pork

a piece of raw salted lean beef

a piece of boiled salted beef

a piece of stale bread

a bunch of raw sliced cabbage.

What precisely was Beaumont hoping to catch in the acrid ocean of the stomach? Data to further the project of medicine? The metaphysical implications of the discoveries could not have passed him by entirely - the popular view of the stomach was as the seat of melancholy. It possessed a maudlin and distinctly masculine sensitivity; associated with wine-skins and wind instruments. There was a potency in its excessive softness: for Hegel the stomach's formlessness aligned it uncomfortably with an amorphous version of the human body taken as a whole: 'the stomach and intestinal canal are themselves nothing other than the outer skin, reversed and developed in peculiar form.' A homunculus of the same stuff as us, but formed in the suspension of physical laws permitted only in the darkest recesses of the human body. This object composed of flesh is reduced only to its capacity to suffer, blush and weep, cowed by an affected shame at the charge of being human.

The St Martin experiments of the 1820s came at a time when new models of human subjectivity brought changes in medical experimentation and demonstration. Surgical dissections had been theatrical affairs, mostly carried out as public events designed to demonstrate the body's function to an audience of students. Dissections would happen in an auditorium, as in the seventeenth century for the pupils of Rembrandt’s Dr Tulp, enthralled by their instructor relieving a dead criminal of a section of flesh. In renaissance Bologna, so public was the affair that dissections were semi-integrated into the programme of events of the city’s Carnival, with some of the audience members in masked costume. In this context, the body was itself like a theatre, with each organ playing a part in the drama of the human mechanism. June Kaminski describes this Cartesian landscape of the body: ‘a biomedical paradigm that presented the body in terms of strict anatomy and structure, reflecting the body as a machine with columns, levers, springs, wedges, pulleys, bellows, sieves, and presses.' The surgeon’s work here is of reflexive revelation: master of internal ceremonies, he draws back the skin like a curtain to a view on the celebrity viscera beneath.

The St Martin experiments in contrast were carried out under unusually intimate conditions, in Beaumont’s own lonely chalet. Beaumont would operate on St Martin exclusively in a domestic setting: curtains of a heavy red, a bed with wire frames and an injured body. Symptomatic, if extreme, of a wider shift at the turn of the 19th century from the act of surgery as a public demonstration to a private operation. Beaumont recorded the process in his personal diary, again rejecting dissection’s formerly operatic mode. As the excerpts show, the diary transcribed the murmurs of St Martin’s stomach from day to day, like those of Werther’s heart in the letters Goethe wrote for him.

The St Martin stoma and their surrounding experiments must therefore be interpreted through a lens of forged confessionalism. Rather than an exposed rectangle of flesh over which the map of common anatomy is easily overlaid, the stoma is a compacted circular crater: a black hole comparable to the mouth or eye, a quasi-sphincter. What is revealed by this opening is no diagram but a formless, mysterious and as yet unthought liquid that possesses in its aggressive causticity a kind of agency. The body revealed by the stoma is not one of signification but subjectification. The unhealed wound can be compared to the viewfinder of a telescope, or a perspective-box: what is revealed to its solitary and intimate spectator is not a pedagogic diagram, but a peepshow. Through the stoma-monocle stretches the stomach’s wet expanse, the basin of the body’s most obscene rivers. This body is no clockwork machine of Vitruvian orthogonals, but a non-Euclidean Zone of unknown composition: body without organs, landscape without coordinates.

In the time of the Romantics, the monads of the enlightenment were being brushed by a solar wind. They were being swept away; gnawed at by the subject of feeling; a being of intensities and inequilibria which threatened to spill over without warning as water from the rim of a cup. This was the body that disclosed itself through St Martin’s stoma; that threatened the eye with a bath in acid. The subject that revolts against its solitude by means of an extreme volatility had found its cousin in the stomach. I could tear open my bosom with vexation, screams Werther, to think how little we are capable of influencing the feelings of each other.

The 19th century was also supposedly a turning point for the emergence of a true empiricism in the medical gaze. More and more, the surgeon abandons his textbooks, becoming a man of ingenuity, of sensibility, of inspiration. As in Beaumont’s case, the surgeon assumes the spontaneity & sophistication of the lover: of the man of feeling. Foucault writes that the Romantic surgeon no longer addresses the body with what can be called a 'gaze’, mediated by discourse, but with the glance: a delicate and cavalier eye cast over an unruly but ready flesh. While 'the gaze implies an open field, and its essential activity is of the successive order of reading', the glance 'instantly distinguishes the essential; it therefore goes beyond what it sees', it is ‘like a finger-pointing’, and 'of the nonverbal order of contact,' - of touching, of feeling.

The progression of the anatomical sciences thus succumbs to eros - surgery as just another carnal calculus giving historical agency to the erect and pointing finger. Yet something more than the procreative impulse was at play when Beaumont offered his finger to the new lips of the stomach. Curiosity had entered here; something like play. Not unlike the sick but harmless satiation for which we offer a finger to the mouth of a toothless puppy. Beaumont treats the stomach like Werther treats his own most pampered organ: 'I treat my heart like a sick child, and gratify its every fancy.' The fingers that pressed aside the flap of St Martin's wound were not those of the skeptic (of the Doubting Thomas), but sought greater intimacies with the exotic reaches of the human. Science was stained by the pursuit of strange new pleasures, a freewheeling experimentation yielding no answers.

After the late 18th century revolutions in both America & France, the surgical discipline acquired a new slogan and a new ethos: ‘Medicine in Liberty.' Throw away your books, doctors! Close the theatres, read flesh by candlelight! In I Sing the Body Electric, Walt Whitman offers a variation on the theme: 'Examine these limbs, red, black, or white, they are cunning in tendon and nerve. They shall be stript that you may see them.' Flaying becomes a disclosure of life, and thus a perverse end in itself - in the tendons & muscles of the body Whitman saw liberty as the polychrome striations of a national flag. But Beaumont's first gaze inside the nakedness of the stomach: the pioneer’s gaze on new territory. No code returned, no map: only a grave, wan faciality.

The stomach is indeed naturally borderless. To weep and spill is the stomach's indigenous form of expression, and soon the St Martin stoma is sure to evolve, like a pineal eye, in men in general. Samuel Taylor Coleridge asked whether 'Tears [are not] analogous...to the watering of the mouth? Is there not some connection between the Stomach and the lachrymal Ducts?' Much like Werther, the stomach can express nothing but a quantitative flush of emotion: the relative fullness or emptiness ambiguously proposed by a black hole, either the dwelling-place of an elusive subjectivity or the beginning of a limitless fall.

So - free the stomach with a bullet! Let him breathe! Cover the body with more inscriptions and more instructions for touching. Forget prosthetics and other enhancements for action, let's make of our bodies not weapon but flag. The dead body of Werther and the weakened, experimental body of St Martin had in common a sacrifice of action in order to become surfaces for reading, figures, scripts so charismatic and obvious as to make the obscurity of the haruspex seem laughable. Werther had the last laugh - his body became his motto, expressed in anatomical allegory. His cry of 'I have so much in me!,' could not have been expressed so forcefully but in his state of determined half-death - heart still ticking, vegetised brain still whirring in paralysis. St Martin's case was perhaps more sinister: his depths were revealed to himself, living, wholly unexpectedly, in a circuit of self-reflexivity to which few can aspire.