I. MIRACOLO, OR DON JUAN

Almost 10 years have passed since I had first come to visit Raphael. Back then, I’d meant to leave Rome after a week, but when the time came, I hadn't yet found a reason to leave, and so decided to stay. Things carried along like this for a while, the two of us sitting in silence on his balcony in the afternoons, spitting out apricot pits onto the street;

‘Did you say something?’ - ‘No, why?’ - ‘Oh, I thought you did.’ - ‘Nope, nothing’; life was good.

A few months later, I took a job in a university library, and learned Italian by watching game shows in the evenings. When we’d first met, Raphael was still trying to make it as a playwright back in London, but had since given that up, and, without any bitterness at all, found work in a letter sorting office. One morning I woke up remembering that it was the second anniversary of me coming to see him. I remembered him picking me up from the airport that day; me waiting in the parking lot outside, watching the seagulls in the distance, circling each other in wild, noiseless corkscrews through the air; a little closer, Raphael’s silhouette against the sky. Even from a distance, I could tell he already didn’t know exactly what to say. I would learn to love him for this. When he got close enough, I remember taking him by the hand, and he, caught off guard, let it go limp inside my palm - I, taking this as a sign of his discomfort, quietly let go and watched it fall back by his side, dangling like a little leather purse. I mentioned all this to him in the kitchen over breakfast and asked if he wanted to do anything. He said he wanted to marry me; the wedding was six months later.

After that came the dog: Rosa, a German Shepherd, adopted from the pound, already approaching old age, sunbathing on the front stoop. The next year, we decided we wanted children and I fell pregnant on the first try - with twins, no less! I gave birth in the flat and, three times that night, passed out from the pain - he thought I was going to die - but by that evening, had two newborns cradled in my lap, one under each arm. One boy and one girl - yes, life springing off me!

The next morning, one of the trees that lined the street outside had collapsed out of nowhere and crushed the front window of somebody’s car; Raphael and I had been watching from the balcony, each clutching a child to our breast, and he explained it must of had something to with the flooding we had had a few weeks before. I was still exhausted, only half listening, and remember myself interrupting to say:/

‘But in such fine weather..’

And then he let me know the boy had started crying.

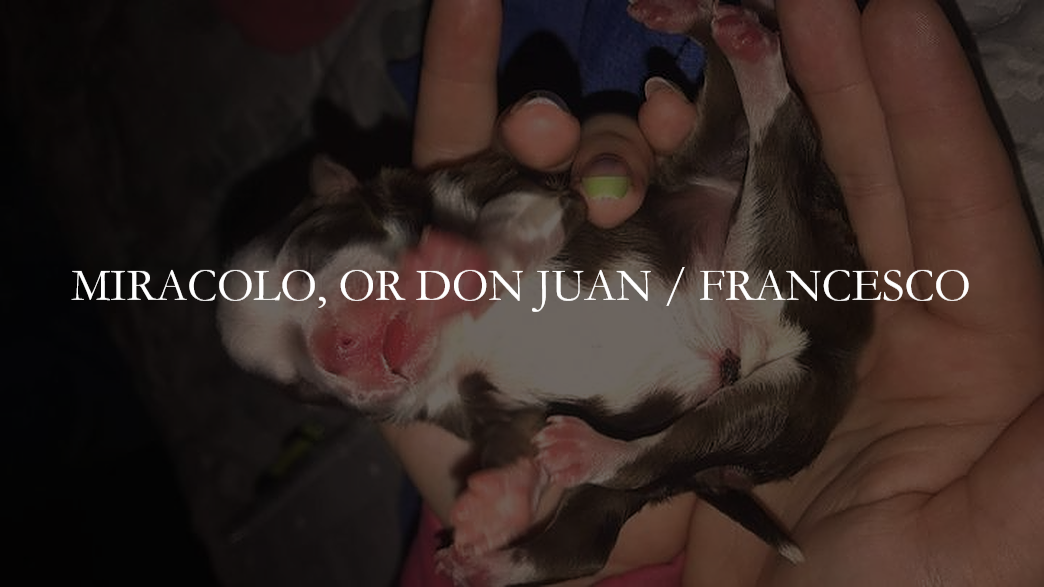

One day, about eight years later, once the two had grown up somewhat, and had even learned to talk, my son was tugging gently at my sleeve and asked why Rosa had gotten so fat - as she walked, her belly was swaying between her legs. She was pregnant too, and that summer, gave birth to a litter of nine puppies, all of which we managed to give away, except the last, who, by some ugly mystery, had been born with six legs and two tails - a tiny chimera.

I called out to Sophia, my little girl, who had been hiding in her bedroom - not quite so happy as her brother to watch the contents of Rosa’s belly spilled out on the kitchen floor:

‘Sophia! One of the puppies has six legs!’

‘Six!’

And she ran in from the other room, standing in the doorway, still a little uneasy:

‘Yes Sophia, six legs - and two tails, as well.’

‘One of the puppies?’

‘Yes, one of the puppies.’

‘Wow.. a puppy with six legs and two tails. How special!'

With that, she peered around my legs and, with such shyness, crept over to go see the little creature for herself, crouching on her knees and running her index finger gently along the top of his head.

‘Wow..’, she repeated, rolling the words against the top of her mouth, ‘a puppy with six legs…’

It was a miracle, the vet had told us, that he had survived childbirth. It was for this reason that, by Sophia’s suggestion, he came to be called Miracolo - ‘miracle’, in Italian. There was even an article about him in a local newspaper, accompanied by a picture of Sophia, smiling, and holding him up to the camera; he, still pink and blind, squirming in her arms. As he grew older, Miracolo took a particular liking to the female members of the household, insisting on sleeping at Sophia’s side, his head resting on her belly, and at breakfast in the morning, under the table, with both tails wagging in the air, and his two back legs trailing limp along the floor behind him, would scurry between me and her, kissing us on the feet - a habit for which Raphael had affectionately nicknamed him ‘Don Juan.’

‘He’s such a little freak, isn’t he?’ Raphael had once laughed, and Sophia, suddenly very serious, as if speaking from the pulpit, answered back - ‘Never talk like that. God is making everything exactly how He likes it.’ All of us were quite taken aback at this; it was the first time, I thought, that I had heard God mentioned in our home.

Miracolo’s presence had turned Sophia into a little abbess, following him around the house, walking the way one walks through a church or a museum, with slow, sober footsteps, and watching over him while he went bounding on ahead, his tongue hanging loose over his bottom lip - she, always smiling faintly, like the Madonna in a Nativity painting; so serene.

One morning, I woke up early and ate breakfast alone - black coffee, a bowl of oatmeal, half a grapefruit - and half-way through, realised that not once had I felt Miracolo’s wet nose against my ankle, or his paws pressed against my toes. Under the table, he was lying flat on his stomach, all six legs splayed out across the tiles. Invisibly, over the last few weeks, his life - that brief and funny thing - had been coming to a close. Sophia, somehow, had been the only one who knew this, even from the start, and had looked at him always with the tender resignation with which one might look up at a loved one waving goodbye from the prow of an ocean liner, pulling away from the harbour.

His body, still so little, fit wrapped up inside a serviette, with only his two tails and two back paws escaping at the bottom, and was buried in the garden that afternoon - food for the spring. Even Raphael (who, initially, had suggested the family keep one of the healthy puppies, and found himself outvoted three to one) was moved to tears, and on a piece of scrap wood, had made up a headstone. It read:

MIRACOLO, OR DON JUAN

2018-2019

Today, 2 years later, the four of us - me, Raphael, and the twins - have taken a trip to the beach. Last week, there was a story in the newspaper about a brother and sister, near Ravenna, who had gone swimming in the ocean together one night. The brother had found himself caught in an undercurrent, and the sister, peering down at him from the top of a boulder, had taken off her dress to twist into a rope by which to pull him up. Tragically, he only succeeded in pulling her in with him, and the two had both died kicking against each other’s bodies, buried under the rolling tide. Raphael, skimming through the paper that morning, had only briefly seen the picture of the ocean beating against the cliff face, under the long shadow of which the pair had drowned (the parents had refused to let pictures of the children appear in print), and, naturally assuming this was probably an article about beach holidays, suggested we make the trip ourselves the next weekend. He’s put on a great deal of weight since we first met, and the Roman sun has turned his whole body bright pink. Sitting back in a deck chair in his swimming trunks, flicking through a magazine, he looks a little like a huge piece of fruit - a peach maybe, or a grapefruit. At my feet, my only son, sitting on his knees, running his index finger across the sand, etching out a nine-pointed star just beside Rosa’s stomach;

‘What are you drawing?’

‘It’s Miracolo.’

‘Miracolo?’

‘Yes Mummy - Miracolo’

Yes - and then I saw it: the one head, the six legs, the two tails - that came to nine points; Miracolo, our nine-pointed star, born under the low arch of Rosa’s belly, exploding quietly in space and shot out into the wet earth. Yes, how perfect - a star for nine-pointed Miracolo. Miracolo who I loved because nature gave him six legs and two tails and still he was born and was happy - ‘impossible, and yet there be was!’ Miracolo, who needed exactly six legs because he never learnt to walk on four, and who was glad because six was exactly as many as he had; our Don Juan, the miracle birth. I had to stop myself from crying.

‘Ah! And there he is! So beautiful!’

‘I thought so too Mummy, I think so too!’

In the distance, Sophia, standing by the shore in a yellow dress, watching the tide swallow her feet as it rolled up the beach, carving little rivulets between her toes. The sun is falling on her head like water. She turns back; I wave; she waves back, smiling faintly.

_______________

II. FRANCESCO

When we were twelve, my twin brother was knocked over by a motorbike and smashed his skull open on the concrete. His brain stopped working and he forgot how to breathe. He had to spend three months in the hospital on a respirator, learning all over again. And it was so hard because, there we were, gathered around the bed, breathing without thinking and without knowing how to teach him - and him watching our shoulders rising and falling with tears in his eyes, not understanding how it had ever been so easy. I remember the day he came home again; me and my mother had made him a cake that morning, almost dancing, barefoot around the kitchen, so excited to see him, and he, without realising, coughed up two great lumps of spittle, blowing out the candles; nobody minded - we were all too happy, and he was smiling so wide. Out of his mouth, from then on, that thick rubber tongue would peek out from between his two front teeth, gulping at the air the way a dog laps up a puddle. At the end of the summer, my parents sat me down and explained he wouldn't be in my class at school anymore; he was going to school somewhere else where they would know better how to take care of him and keep him from getting his clothes dirty. That was how it went; as the years went on, he watched me pass my exams and pick up work in a cafe on the weekends and go to university and struggled to understand how learning to grow up had ever been so easy; still, I didn't know how to teach him. But there he always was, watching over my shoulder as I did my homework or packed my bags to leave, studying my movements, watching me the way, when we were children, we’d go the aquarium and watch the clownfish swirl about the coral with our noses pressed against the glass; watching without coming any closer. And, always, with that thick, rubber tongue hanging loose over his bottom lip.

My mother called last week and told me how well he was doing. They have a new dog, another German shepherd, which he loves more than anything; the two of them even go for walks together in the mornings now - all by themselves. He’s a lot better these days, she loves to tell me. I mentioned I would name my baby after him. ‘The baby!’, she said, as if only just remembering. ‘That’ll make him so happy - he’s been so excited to have a nephew, you know. It’s all he talks about. Sophia, did I tell you, he used the word ‘foetus’ the other day? That’s very advanced isn’t it? Foetus. And he said it like it was nothing - we were just talking about the baby over lunch and then there he was, sitting at the table, saying ‘foetus’. Yes, that’ll make him so happy, you should come over for dinner and let him know.’

My brother’s name is Francesco.

Tonight I’m lying splayed out on the beach with my hand resting on the curve of my belly - nineteen and pregnant and alone, with the tide licking at the soles of my feet. Me and my baby together by the ocean that would swallow us both. When I was little, I remember being given a book with pictures of all the creatures that live down at the bottom of the sea, all bulging eyes and quivering antennae, swimming in water like black petroleum: water that the light won’t dare touch. That’s a little like how I imagine the baby now, floating in that blind ocean just under my stomach, holding fast to the placenta the way tubeworms cling to hydrothermal vents, belching out sulphur in the dark.

And now the sky is going black and there’s a fog settling over the beach: soft as spittle. Reflected across the surface of the water, the lights in the firmament, bobbing atop the waves: little sparkling embryos, pickling in formaldehyde.

If I were born with three legs I would count all of them as precious because nobody would teach me how to walk on two; and it’s like Heaven, where the Good and the Necessary are one, where everything that exists is perfect. So the miracle birth of a child with three legs announces that Heaven is not so terribly far away, that the Kingdom of God is amongst us. To work the miracle is to give the world what it does not want but will learn to need, and for that reason, the miraculous and the ugly go through the world joined at the hip, like Siamese twins.

The prophet Isaiah, speaking of the Messiah yet to come: ‘He had no form or beauty. He was a man in suffering and knew how to bear illness. His face was turned away and He was dishonoured and not esteemed.’ And Saint Andrew of Crete tells us the Savior was a hunchback. Imagine how humiliated one has to be to kiss a leper on the hand.

Once I read about a church in Poland where a communion wafer that had been dropped on the ground was found a few days later, marked with a little red dot. Scientific analysis revealed that the blemish had ‘similarities with human heart tissue with alterations that often appear during the agony’ - how totally obscene! But I have to want it more than air.

Yes; the miracle is ugly but it is something we will learn to need. Because we cannot live on bread alone. Everything that is strictly necessary is not enough: there has to be something senseless. So what I want more than anything is to give myself what I don’t yet know to want; what I want is the miracle birth, and a child at my bosom to run free and senseless on three legs.

And I am so lucky because my birth pangs are at hand; from out of that waterlogged inner chamber, I hear the baby calling ‘Be patient with me, still approaching, almost with you..’, and, opening my thighs toward the ocean, I call back, ‘Be patient with me too, Francesco, almost ready to receive you, ready to press you to my breast and give you everything I can hold in a clenched jaw.’

First, that thick, rubber head, poking out from between my legs - the gaping jaw, the eyes like black onyx - then the body, long and wet and cold, slipping out from the womb in spasms, gills flaring and fins kicking wild against the sand; at last, the tail, slapping hard on my thighs as Francesco slithers down the beach and into the ocean; until, finally, there he was. Just like that - impossible and yet there he was! - my firstborn son, the lungfish, my miracle birth, free at last, learning how to breathe in the shallow water; and there I was, fat and naked and empty as the tomb - and, with such tenderness, dipping my hand into the ocean, watching Francesco coil that thick, rubber head of his around my index finger - both of us, smiling, faintly.